On the 11th of January 2021, Krakul’s contribution to NASA’s Artemis lunar program was officially announced. Crystalspace, partnered with Krakul and Tartu Observatory of Tartu University, has been selected by Maxar Technologies, to build two cameras that will act as a stereo pair to monitor the operations of a robotic arm that will collect regolith samples from the Moon.

This is undoubtedly a massive step for the Estonian space industry. When the launch of ESTCube-1 made Estonia a space nation in 2013, then NASA using technology designed and produced in Estonia by Estonian engineers means that Estonia is well on its way to becoming a real player in the space industry.

But Estonia’s success in space isn’t just an anomaly. Remarkably, for a country with only 1.3 million people, space technology and astronomy has had a long history.

19th century – Beginning of space research in Estonia

Tartu Observatory was founded in 1812, as the first observatory in Estonia. Two years later, a world-renowned astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Struve, who is best known for his observation of double stars, began his research. One of his more notable works includes being the first astronomer to accurately measure the star Vega’s distance from the solar system.

Old Tartu Observatory in 1821. Credit: Tartu University

The 19th century can be marked as the beginning of space research in Estonia, but at the same time, it doesn’t say a lot about Estonians and space. When Tartu Observatory was founded, Estonia did not exist as a country but as a province of the Russian Empire. Furthermore, Estonians didn’t even call themselves Estonians yet (not until the year 1857), and in the year 1812 were still subjected to serfdom, which made higher education almost impossible for the natives.

1918-1940 – Estonian astronomy

After the independence of Estonia in the year 1918, Tartu Observatory remained as the centre for Estonia’s astronomy and meteorology research. During this time, two notable advancements took place:

In 1919, Tartu Observatory became the only institution in Estonia forecasting weather.

Three years later, in 1922, Ernst Öpik, considered one of the first founders of Estonian astronomy, was the first astronomer to measure the Andromeda galaxy’s distance. His works didn’t end there. In the same year, he remarkably predicted the correct frequency of craters in Mars, long before space probes were invented. Later in 1932, he postulated a theory concerning the origins of comets in our solar system. He believed that they originated in a cloud orbiting far beyond Pluto’s orbit, which is now known as the Oort cloud or the Öpik-Oort Cloud in his honour.

Ernst Öpik. Credit: Tartu University Museum

1940-1991 – Estonia and the Soviet Union’s space program

After World War II, Estonia became occupied by the Soviet Union. Even though science mostly became politicised and heavily restricted, the leading research centres, namely Tartu University (of which Tartu Observatory is a part) and Tallinn Polytechnic Institute, continued working.

It was an exciting time for the space industry since the Soviet Union soon became active in a fierce space race with the USA. And Estonia did have a small part in it.

For one, Tartu Observatory continued advancing Estonian astronomy. From the Soviet period, they were the most notable for their research into noctilucent clouds, which are tenuous cloud-like phenomena in the Earth’s upper atmosphere, consisting of ice crystals.

Noctilucent clouds. Credit: NASA

But Tartu Observatory also directly played a role in the development of the Soviet Union’s first satellites. After the launch of Sputnik-1, the Soviets had not developed a sufficient network of facilities to observe satellites. So universities were tasked to start rapidly establishing satellite observation stations. One of them was founded in Tartu during the end of the 1950s.

In about ten years, Tartu Observatory got a chance to develop technology for the space program. Namely, researchers started making sensors that detected UV light from stars which could be deployed to satellites and other spacecraft. They were sent to space on the 18th of April 1968. This can be considered as the first object Estonians ever launched into space.

New Tartu Observatory main building in Tõravere, finished in 1963. Credit: Tartu University

It has been speculated that researchers from the Tallinn Polytechnic Institute (today known as TalTech) also had a direct impact on the Soviet space program. Namely, professor Uno Liiv’s research into the non-stationary fluid discharge. Uno Liiv was offered to target his research for the benefit of the Soviet space industry. And even though the Soviet Union operated under a veil of secrecy, the Tallinn Polytechnic Institute’s measurement tools for fluid discharge might have been used in Soviet space shuttles for fuel-efficiency optimisation.

Another quirky way Estonians helped advance the Soviet space program was through space food. During the start of the Cold War’s space race, the Soviets did not yet have the means to sterilise food efficiently, which complicated keeping astronauts in orbit for more extended periods.

A factory in Estonia, Põltsamaa, had started to develop tube food, mainly for mustard, pâté, and marmalade. The act of tubing food was an innovative approach at the time since it drastically improved food items’ shelf life. So the word about Estonia’s miracle factory reached Moscow and in 1962, the factory started to develop actual space food for Soviet astronauts.

Tubed marmalade by Põltsamaa. Credit: Nami-Nami

1991 – 2021 Rise of the Estonian space industry

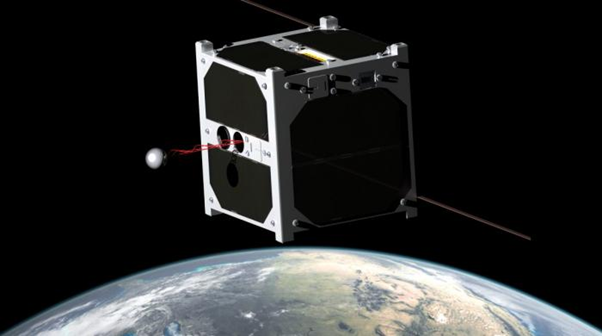

In 2013, Estonia launched its first satellite ESTCube-1 into orbit, officially gaining the title of a space country.

ESTCube, in essence, was a student project started by the University of Tartu in 2008. Aiming to develop young engineers’ skills and jump-start the Estonian space industry, the project united about 200 students and researchers from all significant Estonian universities. The idea was to create a miniature cube satellite that could take pictures from the atmosphere. And also test the concept of an electric, solar wind sail.

ESTCube-1. Credit: Estcube

Even though the solar wind sail test failed, the project was a huge success. It served as the first milestone of independent Estonia’s space industry, and the project provided research material for about 14 publications, 50 scientific presentations and gave birth to 4 spin-off companies. One of those companies was Krakul. Krakul’s founder Markus Järve and current software lead Jaan Viru served as core team members of ESTCube-1.

In 2015, Estonia was officially accepted as the 21st member country of the European Space Agency thanks to ESTCube-1 and Estonia’s historical presence in the space industry. 2 years later, the ESA business incubation centre was founded in Tartu and Tallinn to accelerate space technology startups.

Throughout 2019-2020, TalTech launched their two first cube satellites into space – Koit and Hämarik. Koit was launched into space on the 5th of July 2019, and Hämarik followed a year later, on the 3rd of September 2020. The satellites’ purpose was similar to ESTCube-1, to develop young engineers’ skills and advance Estonia’s space industry. Both satellites functioned as Earth monitoring devices and served as subjects for numerous scientific experiments.

TalTech’s satellite Hämarik. Credit: TalTech

In 2021, the Estonian space industry took a giant leap. On the 11th of January 2021, it was announced, that Estonians will provide stereo cameras to Maxar Technologies for NASA’s Artemis lunar program.

The cameras will pave the way for NASA’s future ambitions – sending people back to the Moon in 2024 and developing the first lunar base.

Custom-made stereo cameras built for NASA’s lunar mission. From the left: Mihkel Pajusalu, Jaan Viru and Jaan Hendrik Murumets

The Estonian space industry is a story of causality. Without the groundwork laid by Tartu Observatory, the ESTCube-1 project would not have taken place. Without the ESTCube project, Estonia wouldn’t have become a member country of the European Space Agency, and spin-off companies Krakul and Crystalspace would not have formed. And without ESTCube-1, TalTech’s first satellites might have looked very different.

Estonia’s next success story could very much be related to space. With constant advancements during the last decade, one can only assume that there are still more significant accomplishments waiting for Estonian engineers.

Follow us on Facebook, LinkedIn, or Instagram to keep up to date with major advancements in the Estonian space industry!

Contact:

press@krakul.eu